Blockchain Weakness Classification (BWC)

A taxonomy for classifying smart contract vulnerabilities.

Last Update: Feb 2 2026

Authors: @BBHGuild

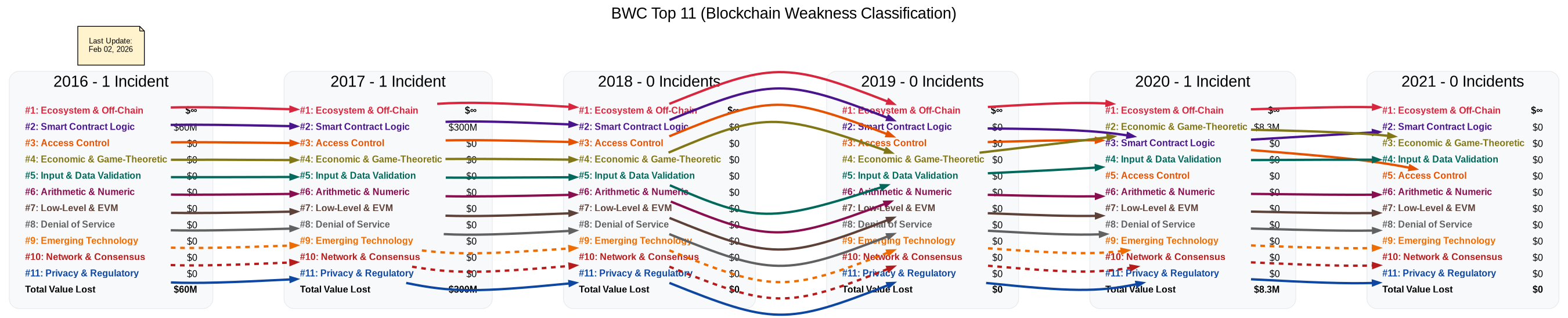

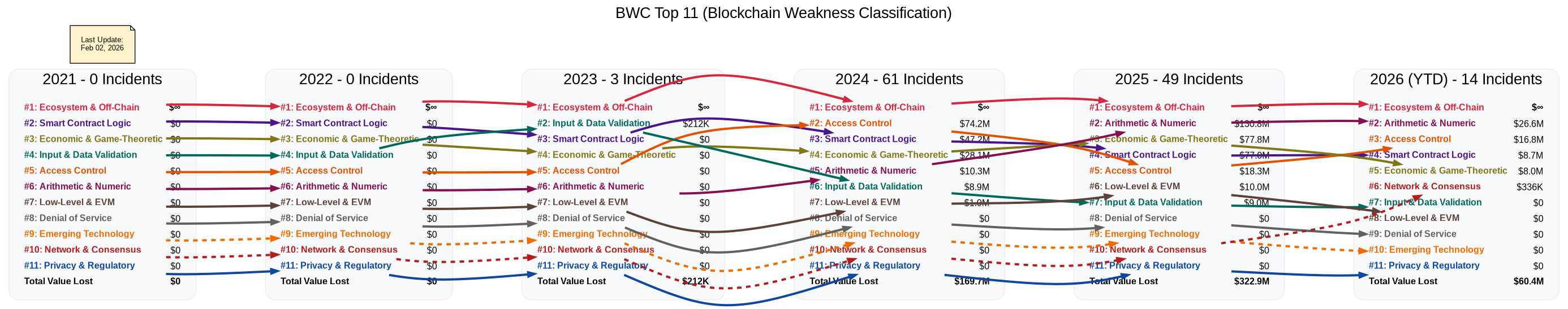

BWC Top 11

| Blockchain Weakness Classification | Description | Exploit Methods | Mitigation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

BWC 1: Ecosystem & Off-Chain Risks | BWC 1.1: Foundational Design Flaws (Trustlessness) | BWC 1.1.1: Indispensable Intermediaries | The system violates the "No Indispensable Intermediaries" law. It relies on specific actors (sequencers, relayers, provers, admin keys) that cannot be replaced by an ordinary participant. If these actors misbehave or disappear, the system halts or censors. | ||

BWC 1.1.2: Barriers to Verification (The Specialist Gap) | The system is theoretically open but practically closed due to excessive complexity or resource requirements. This violates the "Accessibility" principle, creating a class system where verification is a privilege for specialists, forcing users to "trust the dashboard." | ||||

BWC 1.1.3: Reliance on Critical Secrets | The system violates the "No Critical Secrets" law. It relies on private information (mempools, off-chain order books, server-side keys) held by a single actor to function or determine state transitions. | ||||

BWC 1.1.4: Forced Delegation (Loss of Sovereignty) | The system replaces Delegation (optional convenience) with Dependence (mandatory reliance). Users cannot interact with the protocol directly but must route through a specific UI, API, or relayer that acts as a landlord. | ||||

BWC 1.1.5: Lack of Credible Neutrality | The base layer discriminates against specific users or use cases. Instead of "math and consensus," the protocol enforces policy, becoming a "Platform" rather than a neutral "Protocol." | ||||

BWC 1.1.6: Unverifiable Outcomes | The system violates the "No Unverifiable Outcomes" law. Effects on the state cannot be strictly reproduced from public data, requiring "Blind Trust" in an oracle or multisig. | ||||

BWC 1.1.7: User Disempowerment & Extractive Design ("Corposlop") | The system prioritizes corporate metrics (market cap, engagement) over user sovereignty. It uses "corporate optimization power" and a "respectable aura" to mask behavior that extracts value from users rather than empowering them. This manifests in four key ways: 1. Attention & Dopamine Extraction: Hijacking attention for short-term engagement (addiction). 2. Surveillance & Data Commodification: Needless data collection to create sellable assets. 3. Walled Gardens: Preventing exit or interoperability (Monopolistic Lock-in). 4. Predatory Financialization: Marketing high-risk gambling as "investing" (Gamblification). | ||||

BWC 1.2: Identity & Key Management Failures | BWC 1.2.1: Compromised Device/OS | Vulnerabilities in user devices or operating systems leading to private key theft, session hijacking, or malicious transaction approvals. | |||

BWC 1.2.2: Private Key Leakage | Accidental or intentional exposure of private keys, granting unauthorized access to funds. | ||||

BWC 1.2.3: Insider Threat | Current or former employees, contractors, or partners intentionally misusing their authorized access to compromise a system. | ||||

BWC 1.2.4: Wrench Attacks | An attacker uses physical violence, coercion, or threats (shifting toward psychological warfare and AI-enhanced tactics) to force a victim to surrender their private keys or assets, bypassing all technical security measures. | Threat Evolution: | |||

BWC 1.2.5: Vulnerable Vanity/Address Generators | Flaws in tools used to create custom, human-readable addresses (e.g., starting with 0xdead...) that result in predictable or non-random private keys. | ||||

BWC 1.3: Social Engineering & Deception | BWC 1.3.1: Social Engineering Exploits | Tricking users into revealing sensitive information or performing actions against their interest through deception. Many modern campaigns are executed via "Drainer-as-a-Service" platforms, where affiliates use sophisticated kits to target users. | |||

BWC 1.3.2: SIM Swap Attack | An attacker illegally obtains a new SIM card for a victim's phone number, allowing them to intercept 2FA codes sent via SMS. | ||||

BWC 1.3.3: Front-End Hijack/Spoofing | Modifying a DApp's web interface to trick users into approving malicious transactions or revealing secrets. Attackers often use advanced "cloaking" to hide malicious payloads from security researchers while presenting them to targeted victims. | ||||

BWC 1.3.4: Fake Wallet Applications | Malicious mobile or desktop apps that impersonate legitimate wallets to steal private keys or seed phrases. | ||||

BWC 1.3.5: Malicious Browser Extensions | Browser extensions that steal secrets or inject malicious scripts into DApp front-ends. | ||||

BWC 1.3.6: Malicious RPC Provider | A custom RPC endpoint that returns false data to trick a user or wallet into signing a malicious transaction. | ||||

BWC 1.3.7: Flawed Off-Chain Infrastructure | Design flaws in critical off-chain components (e.g., keeper bots, oracle nodes) that are essential for protocol health, causing them to fail under stressful or unexpected conditions like high network congestion. | ||||

BWC 1.3.8: Sybil Attacks | A single entity creates a large number of pseudonymous identities to gain a disproportionate advantage in a system. This undermines mechanisms that assume unique participants, such as airdrop distributions, governance voting, and reputation systems. | ||||

BWC 1.4: Infrastructure & Supply Chain Integrity | BWC 1.4.1: Compromised Validator/Node | A validator or node operator is compromised, leading to malicious activities like transaction censorship, reordering, or double-spending. | |||

BWC 1.4.2: DNS Hijacking Attacks | Redirecting traffic from a legitimate DApp website to a fraudulent phishing site by compromising DNS servers. | ||||

BWC 1.4.3: Compromised Communication Platforms | Hijacking of official project accounts (Discord, X/Twitter, Telegram) to post phishing links or spread misinformation. | ||||

BWC 1.4.4: Supply Chain Attacks | Compromises in the development pipeline, including malicious dependencies, backdoored developer tools (compilers, IDEs), or insecure deployment processes. | ||||

BWC 1.4.5: Client Consensus Bug | A bug in a client's implementation of a core protocol rule (e.g., state root computation, block validation) that causes it to fail to reach or maintain consensus with the rest of the network. | ||||

BWC 1.4.6: Client API Bug | A bug in a client's RPC/API layer that returns incorrect or misleading data to users or applications, potentially leading to flawed transactions or an incorrect view of on-chain state. | ||||

BWC 1.4.7: Communication Link Hijacking | Failure to maintain ownership of critical communication links (e.g., social media vanity URLs), allowing scammers to claim the expired links and impersonate the project. This turns all historical references to that link into phishing traps. | ||||

BWC 1.5: Nation-State & Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs) | BWC 1.5.1: Coordinated Multi-Vector Attacks | Sophisticated, large-scale attacks, often attributed to nation-states or organized crime (e.g., Lazarus Group), that combine multiple tactics simultaneously. | |||

BWC 1.5.2: State-Sponsored Infrastructure Compromise | Nation-state actors targeting core internet infrastructure (e.g., DNS, BGP, certificate authorities) to intercept or redirect traffic for entire ecosystems. | ||||

BWC 1.5.3: Geopolitical Economic Warfare | Using blockchain and DeFi protocols as instruments of economic warfare, such as evading sanctions or destabilizing the financial systems of rival states. | ||||

BWC 1.5.4: Cross-Jurisdictional Regulatory Exploitation | Exploiting inconsistencies and loopholes in regulations across different legal jurisdictions to conduct malicious activities that are difficult to prosecute. | ||||

BWC 1.5.5: Geopolitically-Induced Network Stress | The intentional or unintentional creation of extreme market volatility and network congestion stemming from major geopolitical events. This stress can cause cascading failures in critical on-chain and off-chain infrastructure, leading to mass liquidations, oracle failures, and protocol insolvency. | ||||

BWC 2: Access Control Vulnerabilities | BWC 2.1: Missing or Improper Authorization | BWC 2.1.1: Missing Access Control | Failure to implement any or sufficient authorization checks, allowing sensitive functions to be called by any user. | initialize() or setOwner() that was intended to be called only once but was left public. | onlyOwner).internal, private). |

BWC 2.1.2: tx.origin Authorization | Using tx.origin for authorization, which is insecure as it makes the contract vulnerable to phishing attacks where a user is tricked into calling a malicious intermediary contract. | A, which then calls the vulnerable contract B. Inside B, a check for tx.origin == victim_address passes, granting A the victim's privileges. | msg.sender for authorization, as it identifies the immediate caller. | ||

BWC 2.2: Flawed Permission Management | BWC 2.2.1: Unsafe Token Approvals | Granting excessive or indefinite token allowances (ERC20.approve) to smart contracts, which can lead to fund theft if the approved contract is compromised or malicious. | transferFrom to drain the user's wallet. | permit) for gasless, single-transaction approvals. | |

BWC 2.2.2: Misconfigured Proxy | Errors in deploying or managing proxy patterns (like Transparent or UUPS proxies) that can lead to storage collisions, lost implementations, or unauthorized upgrades. | ||||

BWC 2.2.3: Untrusted Arbitrary Calls | The contract allows an attacker to specify the target and calldata for a low-level call (e.g., .call()). This allows the attacker to force the contract to execute any action in its own context, effectively impersonating it. | token.transferFrom(victim, attacker, amount). Since the victim has approved the contract (BWC 2.2.1), the token contract accepts the request.token.transfer(attacker, amount) to drain assets held by the contract itself. | transferFrom or approve. | ||

BWC 2.2.4: Composable Arbitrary Calls | An exploit where composing multiple, individually secure contracts allows an attacker to make a contract perform a malicious, arbitrary call that would not be possible in isolation. | ||||

BWC 2.2.5: Ruggable Contract Design | Architectural design that intentionally allows privileged developers to steal or freeze user funds without warning. | ||||

BWC 2.3: Callback & Hook Vulnerabilities | BWC 2.3.1: Missing Validation in Callbacks | Failure to verify the caller or parameters of a public callback function. These functions (e.g., flashloan receivers, token hooks like onERC1155Received) must act as gatekeepers, but if they fail to authenticate that the caller is the specific trusted contract (e.g., the lending pool or the token contract), an attacker can invoke them directly to spoof events. | onERC1155Received or onERC721Received directly to simulate a deposit and trigger internal accounting logic (e.g., minting wrapper tokens) without actually transferring assets (e.g., the TSURU exploit). | msg.sender: Strictly verify that the caller is the expected token contract or lending pool address. | |

BWC 3: Smart Contract Logic & State Manipulation | BWC 3.1: Reentrancy Attacks | BWC 3.1.1: Standard Reentrancy | An attacker's contract calls back into a vulnerable contract before its state updates are completed, allowing for multiple withdrawals or other exploits. | nonReentrant). | |

BWC 3.1.2: ERC-777 Reentrancy | Exploiting token hooks in the ERC-777 standard (tokensToSend or tokensReceived) to reenter contracts during a token transfer. | tokensReceived hook on the malicious contract calls back into the victim contract. | |||

BWC 3.1.3: Read-only Reentrancy | Reentering a contract to read a state that is inconsistent or in the process of being changed, leading to logic errors, even if no state is written in the second call. | ||||

BWC 3.1.4: Composable Reentrancy | A reentrancy attack that becomes possible due to unforeseen interactions between multiple, otherwise secure, contracts. The vulnerability emerges from the composition of protocols. | ||||

BWC 3.2: Flawed State Management | BWC 3.2.1: Improper Initialization | Contracts deployed with incorrect initial state, missing initialization, or unset flags, often leaving them ownerless or in a vulnerable state. | initialize function on the implementation, allowing an attacker to claim ownership. | ||

BWC 3.2.2: Faulty Contract Checks | Logic errors in mechanisms that check the status or code of other contracts, such as verifying if an address is a contract or not. | extcodesize to check for an EOA, which can be bypassed if the check is performed during contract construction. | address.code.length > 0. | ||

BWC 3.2.3: Forced Ether Balance | Manipulating a contract's Ether balance to disrupt logic that depends on address(this).balance. | selfdestruct(victim_address). | address(this).balance for critical logic. Design contracts to be agnostic to their Ether balance. | ||

BWC 3.2.4: Self Transfers and Transaction Timing Attacks | Exploiting state changes caused by transfers to the same address or by the ordering of transactions within a block. | ||||

BWC 3.2.5: Broken State Adjustment | Errors in logic that are supposed to modify or correct contract state, leading to inconsistent or exploitable conditions. | ||||

BWC 3.2.6: Proxy/Contract Initialization Front-Running | An attacker observes a transaction that deploys a contract and immediately sends a transaction with a higher gas fee to initialize the contract with their own address as the owner. | initialize function before the legitimate deployer does. | |||

BWC 3.2.7: Broken Invariant via Function Overriding | A vulnerability created when a child contract inherits from a parent (e.g., an OpenZeppelin standard) and overrides an internal function. By altering the logic or removing critical checks in the overridden function, the child contract breaks the security assumptions (invariants) of other, non-overridden public functions in the parent contract that rely on the original internal function's behavior. | mint) in a parent contract that relies on an internal function (e.g., _deposit) for a critical check.deposit). | |||

BWC 3.2.8: Faulty Array & List Handling | Logic errors arising from the improper manipulation, validation, or searching of array data structures. This includes failing to sanitize inputs for duplicate entries or using search algorithms (like binary search) on arrays that violate uniqueness assumptions (e.g., duplicate timestamps), leading to incorrect accounting or stale data retrieval. | mapping to track processed items during iteration. | |||

BWC 3.3: Token Standard & Logic Issues | BWC 3.3.1: Double EntryPoint Tokens | Contracts where a native token also has an ERC-20 representation, potentially leading to inconsistent state or accounting if not handled carefully. | |||

BWC 3.3.2: Fee-on-Transfer & Rebase Accounting Issues | Incorrect handling of tokens that deduct fees during transfers or have an elastic supply (rebase tokens), leading to incorrect balance calculations. | X tokens, the recipient will receive X tokens, which is not true for fee-on-transfer tokens. | |||

BWC 3.3.3: Improper Handling of Native Tokens | Errors in managing the blockchain's native currency (e.g., ETH, BNB) alongside other tokens, often related to payable functions or msg.value. | msg.value or fails to check it, leading to over or underpayment. | msg.value in payable functions. | ||

BWC 3.3.4: Weird ERC20 Behaviors | Failure to handle non-standard implementations of the ERC20 interface, such as tokens that do not return a boolean on success for transfer or approve. | transfer on a non-compliant token, and the call succeeds but does not return true, causing the calling contract to revert. | SafeERC20 library, which handles these edge cases. | ||

BWC 3.3.5: EIP Standard Non-Compliance | A contract implements a feature based on a non-token EIP standard (e.g., ERC-3156 for flash loans, ERC-721 for NFTs) but deviates from the standard's required logic. This leads to broken interoperability with other compliant contracts and creates unexpected behaviors or logical flaws. | ||||

BWC 3.4: Governance & System Logic | BWC 3.4.1: DAO Governance Attacks | Exploiting voting mechanisms, proposal processes, or timelocks to pass malicious proposals or seize control of a protocol. | |||

BWC 3.4.2: Flawed Incentive Structures | Exploitable incentive structures or reward calculation errors that allow attackers to claim unfair rewards. This includes design flaws in penalty or slashing mechanisms where the funds are "donated" in a way that allows the penalized attacker to also be the beneficiary, effectively negating the penalty. | ||||

BWC 3.4.3: Bridge Status Mismatch | Inconsistencies between cross-chain bridge endpoints leading to fund loss or transaction failure, often due to one side of the bridge being paused or upgraded while the other is not. | ||||

BWC 4: Input & Data Validation Vulnerabilities | BWC 4.1: Insufficient Input Validation | BWC 4.1.1: Insufficient Input Validation | Failure to properly sanitize or validate transaction inputs, enabling malicious or unexpected data to be processed. This includes missing zero-address checks. | ||

BWC 4.2: Oracle Manipulation & Data Integrity | BWC 4.2.1: Insufficient Oracle Validation | Inadequate verification of external data feeds (e.g., price feeds), allowing manipulation of critical on-chain information. | |||

BWC 4.2.2: Oracle Manipulation | Actively compromising or gaming the data feeds that DApps rely on for external information, often by manipulating the price on a low-liquidity decentralized exchange that an oracle uses as its source. | ||||

BWC 4.3: Cryptographic Signature Flaws | BWC 4.3.1: Missing Signature Validation | Improper or missing verification of cryptographic signatures, enabling transaction forgery or replay attacks. | ECDSA library). | ||

BWC 4.3.2: Incomplete Signature Schemes | Flaws in the implementation of transaction signing cryptography, such as vulnerability to signature malleability or improper use of EIP-712. | ecrecover is not the zero address. | |||

BWC 4.4: Address Spoofing in Meta-Transactions | BWC 4.4.1: ERC-2771 + Multicall | A vulnerability where a contract uses both ERC-2771 for meta-transactions and a Multicall-type contract as its trusted forwarder. If the forwarder does not properly append the original caller's address to the callData of each sub-call, an attacker can control the data that the receiving contract mistakes for the caller's address, thus impersonating any account. | Multicall forwarder, crafting the callData of a sub-call so that its last 20 bytes contain the address of the victim they wish to impersonate (e.g., the contract owner).Multicall contract forwards this callData to the target contract without appending the real msg.sender.ERC2771Context, extracts the last 20 bytes of the received callData, trusting it to be the sender's address. It then grants the attacker the privileges of the impersonated victim. | msg.sender to the end of the callData for all sub-calls (e.g., abi.encodePacked(call.callData, msg.sender)).Multicall and ERC2771Context from libraries like OpenZeppelin, which have patched this specific interaction.Multicall contracts as trusted forwarders. | |

BWC 4.5: Inconsistent Data Interpretation | BWC 4.5.1: Parser Differential / Inconsistent Validation | Occurs when different components or execution paths interpret or validate the same input data differently. This creates a security gap where checks enforced in one context (e.g., immediate execution) are missing or implemented differently in another (e.g., retry logic, off-chain indexing vs on-chain execution). | |||

BWC 5: Economic & Game-Theoretic Vulnerabilities | BWC 5.1: Miner Extractable Value (MEV) Attacks | BWC 5.1.1: Front-Running | Placing a transaction in the queue before a known future transaction to exploit the order of execution. This is often possible when a transaction's input data contains sensitive information (like a password or a solution to a puzzle) that is publicly visible in the mempool. | ||

BWC 5.1.2: Back-Running | Placing a transaction immediately after a targeted transaction to exploit its effects. | ||||

BWC 5.1.3: Sandwich Attacks | Combining front-running and back-running to trap a victim's transaction and extract value. | ||||

BWC 5.2: Price & Liquidity Manipulation | BWC 5.2.1: Price Manipulation | Artificially influencing asset prices through coordinated market actions to exploit DApp mechanisms, liquidate other traders, or create false impressions of market activity. | |||

BWC 5.2.2: First Deposit / Inflation Attack | Exploiting initialization or low-liquidity conditions in liquidity pools or token vaults (e.g., ERC4626) to manipulate the share price and claim a disproportionate share of assets. | ||||

BWC 5.2.3: Hardcoded or Assumed Asset Price | Using a fixed, hardcoded price for an asset, or implicitly assuming a fixed price ratio (e.g., assuming 1 USDC = 1 USD), instead of using a dynamic oracle feed. This creates arbitrage opportunities when the asset's real market price deviates from the assumed price. | ||||

BWC 5.2.4: Over-Leverage & Liquidation Spirals | The protocol's design encourages or allows for excessive leverage, making the system fragile and susceptible to cascading liquidations ("death spirals") during periods of high market volatility. The risk is amplified when the collateral used is itself volatile, illiquid, or subject to de-pegging. | ||||

BWC 5.3: Transaction Execution Risks | BWC 5.3.1: Lack of Slippage Control | Missing or insufficient protection against price movement between the time a transaction is submitted and when it is executed, making it vulnerable to sandwich attacks. | |||

BWC 5.4: Systemic & Network-Level Economic Risks | BWC 5.4.1: Cascade Failure from Network Congestion | A systemic failure where extreme network congestion (leading to high gas fees) and rapid asset price volatility cause critical off-chain infrastructure (like oracles and keeper bots) to fail or lag. This can lead to cascading liquidations, failed auctions, or other unintended economic consequences because the system's assumptions about timely and affordable transaction inclusion are violated. | |||

BWC 6: Arithmetic & Numeric Vulnerabilities | BWC 6.1: Integer Overflow & Underflow | Exceeding the maximum or minimum value for an integer type, causing it to wrap around. | SafeMath for older Solidity versions. | ||

BWC 6.2: Precision Loss & Rounding Errors | Issues arising from integer division, order of operations (division before multiplication), or inconsistent decimal scaling. | ||||

BWC 6.3: Unsafe Type Casting | Improper or unchecked conversion between numeric types, potentially leading to overflow or precision loss. | uint256 to a uint128 without checking if the value fits, leading to truncation and unexpected behavior. | |||

BWC 6.4: Calculation Errors | General mathematical mistakes in contract logic, such as in liquidity or reward formulas. | ||||

BWC 6.5: Inconsistent Scaling Bugs | Occurs when a smart contract performs math on numbers that have different decimal precisions (e.g., mixing a token with 6 decimals and one with 18) without proper normalization. | ||||

BWC 7: Low-Level & EVM-Specific Vulnerabilities | BWC 7.1: Unchecked Return Values | Failing to verify the success status of external calls, leading the contract to incorrectly assume success when the call actually failed. | ERC20.approve() but doesn't check the boolean return value. The approval fails silently, but the contract proceeds as if it succeeded. | SafeERC20 library, which handles return value checks.success boolean returned from low-level calls. | |

BWC 7.2: Unsafe Storage & Memory Handling | BWC 7.2.1: Unsafe Storage Use | Improper handling of contract storage slots, leading to collisions or data corruption, especially in proxy patterns. | |||

BWC 7.2.2: Improper Deletion of Complex Types | Vulnerabilities arising from the improper deletion of complex data types (e.g., arrays of mappings, structs containing mappings). Operations like delete may not clear the underlying storage for nested mappings, leading to old data persisting and being misinterpreted later. | ||||

BWC 7.2.3: Broken EIP-1153 Transient Storage Use | Misuse of transient storage (TSTORE, TLOAD), which can enable reentrancy or state corruption due to improper clearing or assumptions about its lifecycle. | ||||

BWC 7.3: Weak Cryptographic Primitives | BWC 7.3.1: Weak Random Number Generation | Using predictable or manipulable sources of on-chain entropy (e.g., block.timestamp, blockhash). | block.timestamp to determine the winner, allowing a miner to influence the outcome. | ||

BWC 7.3.2: Malleable ecrecover | Vulnerabilities in signature recovery (ecrecover) allowing for signature reuse or forgery if not handled correctly. | ECDSA library, which protects against signature malleability. | |||

BWC 7.3.3: Second PreImage Attacks | Cryptographic vulnerabilities allowing for collisions in hash functions used by the contract, although this is generally considered infeasible with modern hash functions like SHA-256. | keccak256). | |||

BWC 7.3.4: Forgetting to Blind Polynomials in ZK Protocols | Weaknesses in zero-knowledge proof implementations that expose underlying data by failing to properly randomize cryptographic commitments. | ||||

BWC 7.3.5: Insecure Cryptographic Construction | Using sound cryptographic primitives (e.g., keccak256) but combining them in a way that creates a flawed or insecure algorithm. This is a design-level cryptographic flaw rather than a weakness in the primitive itself. | ||||

BWC 7.4: Client & Compiler Correctness | BWC 7.4.1: Incorrect VM Gas Charges | Logic that becomes vulnerable due to miscalculations of transaction execution costs or changes in gas costs from network upgrades. | |||

BWC 7.4.2: Compiler Bug | A bug in the compiler that causes it to generate incorrect bytecode, or vulnerabilities arising from improper compiler version management. | ^0.8.0) allows a contract to be deployed with different compiler versions, some of which may contain bugs. | pragma solidity 0.8.21;) in source code to ensure deterministic builds. | ||

BWC 8: Denial of Service (DoS) Vulnerabilities | BWC 8.1: DoS via External Calls | Blocking contract functionality through external calls to malicious or non-functional contracts. This often occurs when using low-gas-forwarding functions like .transfer() to send Ether to a contract that requires more gas for its fallback function than is provided. | .transfer() or .send() to a smart contract wallet (e.g., Gnosis Safe) whose fallback function consumes more than the 2300 gas stipend, causing the transaction to revert. | .transfer() and .send() for sending Ether..call{value: ...}("") instead, as it forwards all available gas. | |

BWC 8.2: DoS via Malicious Receivers | A recipient contract designed to revert or consume excessive gas when receiving tokens or Ether, causing the sender's transaction to fail. | ||||

BWC 8.3: DoS via Non-Reentrant Locks | Exploiting reentrancy guards to permanently or temporarily lock functions if the lock is not properly cleared on all execution paths. | try/catch blocks to ensure reentrancy locks are always cleared, even if an external call fails. | |||

BWC 8.4: DoS via Numeric Calculation | Causing numeric underflows, overflows, or division-by-zero errors that block contract execution. | ||||

BWC 8.5: DoS via Block Gas Limit | Crafting operations that exceed the block gas limit, making certain state transitions impossible, often by making an array or loop too large. | ||||

BWC 8.6: DoS via Hook Griefing | Exploitation of token standard callbacks (e.g., ERC777/721/1155) to cause denial of service by making them revert. | onERC721Received hook, preventing transfers to that address. | |||

BWC 8.7: DoS via Return Data Bomb | Exploitation of unbounded return data from an external call to cause an out-of-gas error when the data is copied to memory. | ||||

BWC 8.8: DoS in Cross-Chain Messaging Protocols | Specific vulnerabilities in protocols like LayerZero or their integrations that can halt message passing or cause messages to be delivered incorrectly. | ||||

BWC 8.9: DoS via Unreliable On-Chain Checks | A denial-of-service attack where an attacker exploits unreliable on-chain data sources or checks to block critical operations. A common example is manipulating the state of an address to make a check like address.codehash return an unexpected value, thereby preventing contract deployment. | bytes32(0) to keccak256(""). | address.codehash to determine if a contract exists. A more reliable check is address.code.length > 0. | ||

BWC 8.10: DoS via Forced Recursion | Occurs when a contract uses a recursive function (a function that calls itself) to iterate through a data structure. An attacker manipulates the contract's state to create an excessively long chain of data (e.g., nodes in a tree, linked list), forcing the recursive function to exceed the EVM's call stack limit (1024 frames). This causes any transaction calling the function to fail, permanently locking funds or functionality. | for, while) over recursive patterns. Iteration does not consume the call stack and is not vulnerable to this attack. | |||

BWC 8.11: DoS via Front-Running (Griefing) | Blocking a user's valid transaction by front-running it to alter the underlying state conditions required for success. Unlike MEV, the attacker does not necessarily profit; the goal is to cause the victim's transaction to revert. A common vector is "Permit Griefing," where an attacker observes a transaction containing a signed permit, extracts the signature, and submits it independently. The permit is executed, consuming the nonce. When the victim's transaction attempts to execute the permit again, it reverts due to the invalid nonce, failing the entire operation. | permit() by submitting the signature separately, causing the user's batch transaction to revert. | permit() in a try/catch block. If the call fails (e.g., nonce already used), verify if the allowance is sufficient and proceed. | ||

BWC 9: Emerging Technology Vulnerabilities | BWC 9.2: AI/ML Integration Attacks | BWC 9.2.1: AI Model Poisoning & Bias Exploits | Vulnerabilities arising from the corruption of an AI/ML model's training data or the exploitation of its inherent biases. This is an attack on the integrity of the model itself. | ||

BWC 9.2.2: AI Prompt Injection & Data Exfiltration | Occurs when a system allows untrusted external data (e.g., emails, calendar invites, web pages) to be interpreted as trusted commands by an AI agent. The AI is "jailbroken" by malicious data, causing it to perform unauthorized actions or leak sensitive information. | ||||

BWC 9.3: Hardware-Level Exploits | Attacks that target the underlying hardware on which nodes or validators run, such as Rowhammer or Spectre, to corrupt memory or leak sensitive data. | ||||

BWC 10: Network & Consensus Evolution Attacks | BWC 10.1: Advanced P2P Network Attacks | Sophisticated attacks on the peer-to-peer networking layer of a blockchain, such as eclipse attacks or network partitioning, to isolate nodes or disrupt consensus. | |||

BWC 10.2: Novel Consensus Mechanism Exploits | Vulnerabilities specific to newer or more complex consensus mechanisms beyond traditional Proof-of-Work or Proof-of-Stake. | ||||

BWC 10.3: Cross-Protocol Interoperability Attacks | Vulnerabilities that emerge from the complex and often unaudited interactions between different blockchain protocols, especially in the context of DeFi composability. | ||||

BWC 10.4: Protocol Upgrade-Induced Vulnerabilities | Vulnerabilities that emerge in previously secure contracts when a network or protocol upgrade (like an EIP implementation) changes the behavior or security assumptions of the underlying platform. The contract code itself doesn't change, but its execution context does, rendering existing security patterns ineffective. | ||||

BWC 10.4.1: EIP-7702 Delegation Risks | With the adoption of EIP-7702, Externally Owned Accounts (EOAs) can temporarily delegate their capabilities to a smart contract. This blurs the line between EOAs and contracts, breaking fundamental security assumptions. For example, the invariant that tx.origin is always an EOA is no longer true, rendering checks like msg.sender == tx.origin unsafe for reentrancy protection. | msg.sender == tx.origin true, bypassing old reentrancy guards.chain_id=0. | nonReentrant modifier) instead of tx.origin checks.initWithSig) or restricting calls to the ERC-4337 EntryPoint.CREATE2 and avoid chain_id=0. | ||

BWC 10.4.2: Constantinople Reentrancy (Deprecated) | A reentrancy vector introduced by a proposed change to SSTORE gas costs in EIP-1283 for the Constantinople hard fork. This change would have made .send() and .transfer() unsafe, breaking a core security assumption for many contracts. The hard fork was delayed to remove this vulnerability. | .send() or .transfer() to call back into the victim contract with enough gas to perform malicious state changes. | |||

BWC 10.4.3: Call Depth Attack (Deprecated) | A historical DoS vector, mitigated by the EIP-150 hard fork, where an attacker could recursively call a contract to exhaust the 1024 call depth limit, causing any subsequent external calls within the transaction to fail. | ||||

BWC 11: Privacy & Regulatory Attack Vectors | BWC 11.1: Privacy Protocol Compromises | BWC 11.1.1: Anonymity Set Failures | The effectiveness of a privacy protocol (especially mixers) relies on a large and diverse set of users to create a "crowd" to hide in. When the number of users or the volume of transactions is low, the anonymity set shrinks, making it easier for observers to statistically link deposits and withdrawals. | ||

BWC 11.1.2: Privacy OPSEC Failures | User-side errors in operational security that undermine the privacy protections offered by a protocol. Even a perfectly designed privacy protocol can be rendered ineffective if the user fails to follow best practices for maintaining their anonymity. | ||||

BWC 11.2: Regulatory Weaponization | BWC 11.2.1: Patent Trolling | Using patents, often acquired for the sole purpose of litigation, to file infringement lawsuits against open-source protocols or developers. The goal is typically to stifle competition, extract settlement fees, or create legal uncertainty, rather than to protect a genuine invention. | |||

BWC 11.2.2: Government Overreach | The use of state power, including sanctions, subpoenas, or regulatory enforcement actions, to target protocols, developers, or users in a manner that exceeds clear legal mandates or stifles innovation. | ||||

BWC 11.2.3: "Code is Law" Defense Exploitation | An attacker performs an economically harmful exploit and subsequently uses the legal argument that their actions were permissible because they were allowed by the smart contract's code. This strategy exploits the difficulty legal systems face in applying traditional statutes for fraud or manipulation to autonomous, decentralized protocols. |

General Principles & Mitigations

This section outlines high-level principles and common technical mitigations that apply broadly across many vulnerability classes. Specific, targeted mitigations can be found in the main table.

Core Security Principles

- Defense in Depth: Assume breach. Layer multiple, independent defenses so the failure of one does not compromise the whole system.

- Minimize Attack Surface: Every line of code is a liability. Reduce complexity by eliminating non-essential features, code, and dependencies to shrink the target for attackers.

- Least Privilege: Grant the absolute minimum permissions for the shortest time necessary. Limit both the scope (what) and duration (how long) of any privilege.

- Security as a Process: Security is a continuous process, not a one-time audit. Actively adapt defenses to the evolving threat landscape through ongoing review and learning.

2026 EVM Contract Vulnerability Incidents Classification & Analysis.

This database uses the BWC to classify Contract Vulnerability Incidents. Note off-chain issues have been excluded they're the most prevalent and resulted in more values lost. Humans remains to be the weakest point human stupidity or ingenuity(depending on how you look at it) could be infinite. It's unfeasible to track it.

2026-02-02 - 14

- Date: 2026-02-02

- Project: Matcha Meta (SwapNet)

- Value Lost: ~$16,800,000

- Chain: Base

- BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 2: Access Control Vulnerabilities - Primary Classification:

BWC 2.2.3: Untrusted Arbitrary Calls - Secondary Classification:

BWC 2.2.1: Unsafe Token Approvals

- Broader Classification:

- Description:

- Matcha Meta's SwapNet router was exploited for ~$16.8M (later analysis suggests ~$17M) due to an arbitrary call vulnerability in a closed-source contract.

- Vulnerability: The SwapNet router failed to validate inputs properly, allowing unauthorized arbitrary calls. The attacker used this to force the contract to call

transferFromon various tokens, draining funds from users who had granted infinite approvals to the router. - Attack Flow:

- Reconnaissance: The attacker identified users with infinite approvals to the SwapNet router.

- Execution: The attacker exploited the arbitrary call flaw to inject calls to

token.transferFrom(victim, attacker, amount), bypassing the router's intended logic. - Laundering: Funds were swapped for USDC (~$10.5M) and then ~3,655 ETH on Base, which was subsequently bridged to Ethereum Mainnet.

- References:

2026-01-26 - 13

- Date: 2026-01-26

- Project: Individual Swap Incident (Illiquid Pool)

- Value Lost: ~$140,000

- Chain: Ethereum

- BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 5: Economic & Game-Theoretic Vulnerabilities - Primary Classification:

BWC 5.3.1: Lack of Slippage Control - Secondary Classification:

BWC 1.3.7: Flawed Off-Chain Infrastructure (Potential UI/Routing Failure)

- Broader Classification:

- Description:

- An individual user suffered a catastrophic loss of ~$140,000 in a single swap transaction, receiving only ~0.09 EUR in return.

- Vulnerability: The transaction was executed through a liquidity pool with insufficient depth (illiquid). The user's transaction likely lacked a proper

amountOutMin(slippage protection) parameter, or the interface used failed to warn/prevent the routing through the empty pool. - Execution: The user attempted to swap a high-value amount of tokens. Due to the lack of liquidity in the selected pool, the trade suffered ~100% price impact. Without a slippage revert, the transaction executed, effectively donating the funds to the pool's liquidity providers or back-running MEV bots.

- References:

2026-01-11 - 12

- Date: 2026-01-11 (Estimated based on report timing)

- Project: MetaverseToken (MT)

- Value Lost: ~$37,000

- Chain: BSC

- BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 5: Economic & Game-Theoretic Vulnerabilities - Primary Classification:

BWC 5.2.1: Price Manipulation

- Broader Classification:

- Description:

- TenArmor detected a suspicious attack involving the MetaverseToken (MT) on BSC, resulting in a loss of approximately $37,000.

- Vulnerability: Limited details were provided, but the incident has been classified as price manipulation based on the detected on-chain behavior.

- Attack Flow: The specific mechanics involved an interaction with the MT contract that drained funds, likely via market manipulation or a flaw in how the token handles price/value calculations.

- References:

2026-01-01 - 11

- Date: 2026-01-01

- Project: Valinity

- Value Lost: ~$63,000

- Chain: Ethereum

- BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 3: Smart Contract Logic & State Manipulation - Primary Classification:

BWC 3.4.2: Flawed Incentive Structures (Flawed Rebalance Logic) - Secondary Classification:

BWC 5.2.1: Price Manipulation (Spot Price Dependency)

- Broader Classification:

- Description:

- Valinity was exploited for ~$63k due to a business logic flaw in its rebalancing mechanism.

- Vulnerability: The

acquireByLTVDisparityfunction, intended to rebalance the syntheticVYtoken holdings based on LTV ratios and Uniswap V3 spot prices, was publicly callable. Crucially, the logic was flawed as it was hardcoded to execute swaps ofVYinto a liquidity pool that held negligible liquidity (~$106 USDC). - Attack Flow:

- Price Manipulation: The attacker swapped USDC for PAXG to artificially increase the PAXG price on Uniswap V3.

- Forced Dump: The attacker called the public

acquireByLTVDisparityfunction. Due to the inflated PAXG price (which altered the LTV calculation), the contract logic triggered a sell-off ofVYtokens into the illiquid pool. - Arbitrage/Borrow: The attacker bought the dumped

VYtokens cheaply from the pool and used them as collateral to borrow hard assets (ETH, BTC, PAXG) from the protocol, exiting with the profit.

- Note: The protocol paused contracts following the exploit.

- References:

2026-01-01 - 10

- Date: 2026-01-01

- Project: PRXVTai

- Value Lost: ~$97,000

- Chain: Base

- BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 3: Smart Contract Logic & State Manipulation - Primary Classification:

BWC 3.4.2: Flawed Incentive Structures (Reward Accounting Mismatch) - Secondary Classification:

BWC 2.3.1: Missing Validation in Callbacks (Missing Token Transfer Hooks)

- Broader Classification:

- Description:

- PRXVTai was exploited for ~$97k on Base due to a flaw in its staking reward mechanics.

- Vulnerability: The

PRXVTStakingcontract minted a transferable receipt token (stPRXVT) representing stakedAgentTokenV2. However, the contract failed to implement the necessary hooks (e.g.,_beforeTokenTransfer) to update reward accounting state variables when these receipt tokens were transferred between users. - Attack Flow:

- Staking/Transfer: The attacker likely staked tokens to receive

stPRXVTor transferredstPRXVTbetween wallets. - Accounting Desync: Because the reward logic (

earned()) calculated rewards based on the current balance but the "reward debt" (oruserRewardPerTokenPaid) was not synchronized during transfers, the system failed to correctly track how long the tokens were held by specific addresses. - Drain: This allowed the attacker to claim inflated rewards, which were then bridged to Ethereum.

- Staking/Transfer: The attacker likely staked tokens to receive

- References:

2026-01-20 - 9

- Date: 2026-01-20

- Project: SynapLogic

- Value Lost: ~$88,000

- Chain: Base

- BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 3: Smart Contract Logic & State Manipulation - Primary Classification:

BWC 3.2.8: Faulty Array & List Handling (Duplicate Entries) - Secondary Classification:

BWC 3.4.2: Flawed Incentive Structures

- Broader Classification:

- Description:

- SynapLogic on Base was exploited for ~$88k due to a logic flaw in its referral system.

- Vulnerability: The

swapExactTokensForETHSupportingFeeOnTransferTokensfunction accepted a user-supplied arrayaddress[] refByto distribute referral rewards (10% per referee) but failed to check for duplicate addresses or cap the total payout percentage. - Attack Flow:

- Duplicate Injection: The attacker called the function with the

refByarray containing their own address repeated 31 times (e.g.,[self, self, ... x31]). - Reward Multiplication: The contract calculated the reward as 31 * 10% = 310% of the input value.

- Drain: The contract paid out the inflated reward in ETH/USDC from its reserves to the attacker, draining the purchasing contract.

- Duplicate Injection: The attacker called the function with the

- Note: The attacker also minted SYP tokens during the process, but these were locked in vesting and could not be sold. The profit was derived solely from draining the contract's liquidity backing the referral payouts.

- References:

2026-01-20 - 8

- Date: 2026-01-20

- Project: MakinaFi

- Value Lost: ~$4,130,000 (1,299 ETH)

- Chain: Ethereum

- BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 5: Economic & Game-Theoretic Vulnerabilities - Primary Classification:

BWC 5.2.1: Price Manipulation (Asset Inflation) - Secondary Classification:

BWC 4.2.2: Oracle Manipulation (Internal Accounting as Oracle)

- Broader Classification:

- Description:

- MakinaFi's DUSD Machine was exploited for ~$4.13M due to a vulnerability in its internal accounting logic.

- Vulnerability: The protocol used a specific Weiroll script to calculate the value of its positions (specifically in the MIM-3CRV Curve pool) to determine the Assets Under Management (AUM). This script relied on spot values that could be manipulated.

- Attack Flow:

- Manipulation: The attacker used large flash loans to inflate the value of the MIM-3CRV pool and the associated rewards.

- AUM Update: The attacker called

updateTotalAum, which ran the vulnerable script. This recorded an artificially inflated value for the protocol's holdings, consequently spiking the price of the DUSD token (which is derived from AUM). - Extraction: The attacker utilized the DUSD/USDC Curve pool (which relies on this internal price) to swap DUSD for USDC at the inflated rate.

- Execution Twist: The original attacker (0x2F93...) deployed the exploit contract but was front-run by an MEV bot (0x935...). The MEV bot replicated the attack logic and secured the funds.

- Status: The protocol is paused (Recovery Mode). The team is negotiating with the MEV builder and a Rocket Pool validator who unintentionally received a portion of the funds to recover the assets.

- References:

2026-01-21 - 7

- Date: 2026-01-21

- Project: SagaEVM (Saga Protocol Chainlet)

- Value Lost: ~$6.8M bridged to Ethereum)

- Chain: SagaEVM / Ethereum

- BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 3: Smart Contract Logic & State Manipulation - Primary Classification:

BWC 3.2.5: Broken State Adjustment (Infinite Mint) - Secondary Classification:

BWC 10.3: Cross-Protocol Interoperability Attacks (IBC Message Validation)

- Broader Classification:

- Description:

- SagaEVM, an EVM-compatible chainlet of the Saga Protocol, was exploited for approximately $7 million, resulting in a chain halt at block height 6593800. The exploit targeted the ecosystem's stablecoin, Saga Dollar ($D).

- Vulnerability: The flaw existed within the chain's precompile bridge contract responsible for handling Inter-Blockchain Communication (IBC). The system failed to properly validate custom payloads, allowing a malicious helper contract to bypass collateral checks and mint infinite $D tokens "out of thin air."

- Attack Flow:

- Injection: The attacker deployed a malicious helper contract (0x7D69...) on SagaEVM.

- Infinite Mint: The helper contract sent crafted IBC messages to the precompile bridge, triggering the unauthorized minting of ~$7M in $D.

- Extraction: The attacker bridged the illicitly minted $D to Ethereum Mainnet via the Squid Router.

- Laundering: On Ethereum, the funds were swapped via 1inch and KyberSwap into ETH (2,000+ ETH), USDC, yUSD, and tBTC. A portion ($800k) was deposited into Uniswap V4 liquidity positions (NFTs).

- Status: SagaEVM remains paused. The Saga SSC mainnet and other chainlets were unaffected. The $D token depegged ~25% following the inflation event.

- Addresses:

- Attacker (Saga/ETH):

0x2044697623AfA31459642708c83f04eCeF8C6ECB - Malicious Helper Contract (Saga):

0x7D69E4376535cf8c1E367418919209f70358581E

- Attacker (Saga/ETH):

- References:

2026-01-12 - 6

- Date: 2026-01-12

- Project: YO Protocol

- Value Lost: ~$3,710,000 (Covered by Protocol Treasury)

- Chain: Ethereum

- BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 5: Economic & Game-Theoretic Vulnerabilities - Primary Classification:

BWC 5.3.1: Lack of Slippage Control - Secondary Classification:

BWC 1.3.7: Flawed Off-Chain Infrastructure

- Broader Classification:

- Description:

- YO Protocol suffered a loss of ~$3.71M during a routine rebalancing operation due to a misconfigured automated swap. The protocol's "Automated Harvesting System" attempted to swap ~$3.84M worth of stkGHO for USDC but received only ~$112k, resulting in a 97% loss.

- Vulnerability: The incident was an operational failure rather than a smart contract exploit. The vault operator (keeper bot) submitted a transaction to the Odos Router with an effectively disabled slippage parameter (set to

17,872,058). The on-chain harvesting logic checked for "execution drift" but failed to validate the sanity of the initial output quote. - Execution: The aggregator, following the permissive instructions, routed the massive trade through fragmented and illiquid Uniswap V4 pools (and others including Curve/Balancer). The route utilized pools with extreme fee tiers (up to 88%) and insufficient liquidity, vaporizing the funds into the hands of LPs positioned in these pools.

- Incident Response: The YO Protocol team utilized their multisig to backstop the loss, purchasing ~3.71M GHO via CoW Swap (which offers MEV protection) and redepositing it into the vault. An on-chain message was sent to the LPs requesting a return of funds in exchange for a 10% bounty.

- References:

2026-01-12 - 5

- Date: 2026-01-12

- Project: dHEDGE

- Value Lost: $0 (Critical Vulnerability Patched; >$10M Risk)

- Chain: Ethereum / Optimism

- BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 4: Input & Data Validation Vulnerabilities - Primary Classification:

BWC 4.5.1: Parser Differential / Inconsistent Validation - Secondary Classification:

BWC 10.3: Cross-Protocol Interoperability Attacks

- Broader Classification:

- Description:

- A critical vulnerability was identified in dHEDGE’s 1inch integration guard that could have allowed a malicious pool manager to bypass slippage protection and drain over $10M in user funds.

- Vulnerability: The issue stemmed from a Parser Differential between the dHEDGE contract guard and the 1inch Router. The dHEDGE guard calculated slippage based on the

tokeninput parameter provided in the function call. However, the 1inchunoswapfunction for Uniswap V3 pools ignores thistokeninput entirely, determining the swap direction (ZeroForOne) solely based on a specific bitmask within thepooluint256 identifier. - Attack Flow:

- Parser Deception: A malicious manager provides a worthless "Fake Token" as the

tokeninput. The dHEDGE guard calculates slippage logic based on this Fake Token (which the attacker controls to ensure checks pass). - Execution Divergence: The manager constructs the

poolidentifier such that the 1inch Router executes a swap of the real pool assets (e.g., USDT) -> Fake Token, ignoring thetokeninput provided in step 1. - Bypass: Because the dHEDGE guard logic assumes the Fake Token is the source asset being swapped, it fails to validate the slippage/outflow of the real USDT, allowing the manager to drain the pool.

- Parser Deception: A malicious manager provides a worthless "Fake Token" as the

- Incident Response: The vulnerability was disclosed by a whitehat researcher following an audit contest where it was initially missed. The protocol developers confirmed the severity and patched the issue before any exploitation occurred.

- References:

2026-01-08 - 4

- Date: 2026-01-08

- Project: TMXTribe

- Value Lost: ~$1,400,000

- Chain: Arbitrum

- BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 3: Smart Contract Logic & State Manipulation - Primary Classification:

BWC 3.4.2: Flawed Incentive Structures - Secondary Classification:

BWC 1.1.2: Barriers to Verification (The Specialist Gap)

- Broader Classification:

- Description:

- TMXTribe, a GMX fork, was exploited for approximately $1.4M over a 36-hour period due to flawed logic in its unverified contracts. The attack involved a loop of minting and staking TMX LP tokens using USDT, swapping the deposited USDT for USDG (the protocol's stablecoin), unstaking, and draining the acquired USDG.

- Vulnerability: The specific root cause was a logic bug in the LP staking and swapping mechanics that failed to account for this extraction loop. The contracts were unverified, hiding the exact flaw from independent review.

- Incident Response: Despite the exploit continuing for 36 hours, the team failed to pause the protocol. On-chain activity showed the team deploying and upgrading contracts during the attack but taking no effective action to stop the drainage.

- Addresses:

- Exploiter 1:

0x763a67E4418278f84c04383071fC00165C112661 - Exploiter 2:

0x16Ed3AFf3255FDDB44dAa73B4dE06f0c2E15288d

- Exploiter 1:

- References:

2026-01-08 - 3

- Date: 2026-01-08

- Project: Truebit

- Value Lost: ~$26,600,000

- Chain: Ethereum

- BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 6: Arithmetic & Numeric Vulnerabilities - Primary Classification:

BWC 6.1: Integer Overflow & Underflow

- Broader Classification:

- Description:

- Truebit was exploited for approximately $26.6M due to an integer overflow vulnerability. A malicious actor was able to mint tokens for 0 ETH and subsequently swap them for 8,535 ETH.

- Vulnerability: The

getPurchasePrice()function, responsible for calculating the minting cost, relied on an internal calculation where intermediate values (v9 + v12) overflowed2^256. This overflow caused the price calculation to wrap around and result in zero (after division), allowing the attacker to mint TRU tokens for free. - Attack Flow: The attacker called

AdminUpgradeabilityProxy.buyTRU()to mint 240M tokens for 0 ETH, then calledsellTRU()to drain ETH from the protocol. This process was repeated with increasing amounts. - Addresses:

- Exploiter 1:

0x6C8EC8f14bE7C01672d31CFa5f2CEfeAB2562b50 - Exploiter 2:

0xc0454E545a7A715c6D3627f77bEd376a05182FBc - Protocol Contract:

0x764C64b2A09b09Acb100B80d8c505Aa6a0302EF2

- Exploiter 1:

- References:

2026-01-06 - 2

- Date: 2026-01-06

- Project: IPOR Fusion (USDC Optimizer on Arbitrum)

- Value Lost: ~$336,000

- Chain: Arbitrum

- BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 10: Network & Consensus Evolution Attacks - Primary Classification:

BWC 10.4.1: EIP-7702 Delegation Risks - Secondary Classification:

BWC 4.1.1: Insufficient Input Validation

- Broader Classification:

- Description:

- A legacy IPOR Fusion vault (USDC on Arbitrum) was exploited for ~$336k. The exploit leveraged a "perfect storm" of a legacy vulnerability and a new attack vector introduced by EIP-7702.

- Vulnerability: The incident was caused by the combination of two factors:

- Legacy Logic Error: The specific legacy vault lacked strict validation for "fuses" (logic modules) in its

configureInstantWithdrawalFusesfunction, trusting that only verified addresses would add them. - EIP-7702 Delegation Hijack: An administrator account (

0xd8a1...) had delegated its execution to a helper contract (0xa3cc...) via EIP-7702. This helper contract contained a vulnerability allowing arbitrary calls.

- Legacy Logic Error: The specific legacy vault lacked strict validation for "fuses" (logic modules) in its

- Attack Flow:

- Identity Hijacking: The attacker exploited the arbitrary call vulnerability in the delegated helper contract to force the admin's EOA to call the Vault.

- Malicious Fuse Injection: Acting as the admin, the attacker added a malicious "fuse" to the vault.

- Drain: The attacker triggered

instantWithdraw, causing the vault to execute the malicious fuse code and transfer assets to the attacker.

- Incident Response: IPOR Labs acknowledged the exploit, confirmed it was isolated to this single legacy vault due to its unique configuration, and stated that the IPOR DAO would cover the shortfall from the treasury.

- References:

2026-01-03 - 1

- Date: 2026-01-03

- Project: Flow Blockchain / deBridge / LayerZero

- Value Lost: Undetermined (Significant breakdown in cross-chain accounting; Specific transactions of ~$200k+ cited)

- Chain: Flow, Cross-chain

- BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 1: Ecosystem & Off-Chain Risks - Primary:

BWC 1.1.6: Unverifiable Outcomes(State finality was revoked by decree, not consensus rules). - Secondary:

BWC 1.1.1: Indispensable Intermediaries(The validators acted as "Landlords" deciding who retains assets, failing the Walkaway Test).

- Broader Classification:

- Description:

- Following an undisclosed exploit, the Flow Blockchain team executed a mandatory chain rollback to revert the network state. However, the team allegedly failed to coordinate this action with critical bridge providers (e.g., deBridge, LayerZero), leading to a catastrophic state desynchronization between Flow and the broader ecosystem.

- Centralization Risk: The decision to unilaterally roll back the chain highlights the risks of centralized governance in Layer-1 blockchains, where "finality" can be revoked by the operator.

- Bridge Mismatch (Double Spend & Loss): The rollback created a temporal paradox for cross-chain transactions processed during the rollback window:

- Bridged Out (Double Spend): Users who bridged funds out of Flow had their assets released on the destination chain. The rollback restored their balances on Flow to the pre-transfer state, effectively doubling their funds.

- Bridged In (Total Loss): Users who bridged funds into Flow had their assets locked on the source chain. The rollback erased the crediting transaction on Flow, leaving the users with no assets on either chain.

- References:

It’s important to emphasize that the intent behind this content is not to criticize or blame the affected projects but to provide objective overviews that serve as educational material for the community to learn from and better protect projects in the future.

2025 EVM Contract Vulnerability Incidents Classification & Analysis.

This database uses the BWC to classify Contract Vulnerability Incidents. Note off-chain issues have been excluded they're the most prevalent and resulted in more values lost. Humans remains to be the weakest point human stupidity or ingenuity(depending on how you look at it) could be infinite. It's unfeasible to track it.

2025-12-31 - 6

- Date: 2025-12-29

- Project: Multiple (e.g., Skep-pe) / "Anti-Rug" Vigilante Bot

- Value Lost: Variable (Deployer ETH Locked / Failed Launches)

- Chain: Ethereum

- Actor:

0x5c37ce78b79a09d211f3d35a617f980585e32b3c - BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 8: Denial of Service (DoS) Vulnerabilities - Primary Classification:

BWC 8.11: DoS via Front-Running (Griefing) - Secondary Classification:

BWC 3.2.1: Improper Initialization

- Broader Classification:

- Description:

- A sophisticated "vigilante" bot campaign was identified targeting new token launches (often categorized as "shitcoins") that utilize a specific initialization pattern.

- The Flaw: Many token contracts use a

startTradingoropenTradingfunction that unconditionally callsIUniswapV2Factory.createPair(). The factory reverts if a pair for the token combination already exists. - The Exploit: The bot monitors the mempool for deployers funding their token contracts with ETH in preparation for liquidity addition. The bot then front-runs the deployer's

openTradingtransaction by callingcreatePairon the Uniswap factory directly. - The Impact: When the deployer's transaction attempts to execute, it reverts because the pair now exists. This effectively "bricks" the launch. In many cases, the contracts lack a mechanism to rescue the ETH sent to the contract (or rely on

openTradingto move it), causing the deployer's initial liquidity funds to be permanently locked or "burned." - Code Snippet:

function openTrading() external onlyOwner() { require(!tradingOpen,"trading is already open"); uniswapV2Router = IUniswapV2Router02(0x7a250d5630B4cF539739dF2C5dAcb4c659F2488D); _approve(address(this), address(uniswapV2Router), _tTotal); // VULNERABILITY: The bot calls factory.createPair() before this transaction executes. // This causes the legitimate launch transaction to revert due to the pair already existing. uniswapV2Pair = IUniswapV2Factory(uniswapV2Router.factory()).createPair(address(this), uniswapV2Router.WETH()); uniswapV2Router.addLiquidityETH{value: address(this).balance}(address(this),balanceOf(address(this)),0,0,owner(),block.timestamp); IERC20(uniswapV2Pair).approve(address(uniswapV2Router), type(uint).max); swapEnabled = true; tradingOpen = true; }

- References:

2025-12-29 - 5

- Date: 2025-12-29

- Project: MSCST (Staking Contract) / GPC Token

- Value Lost: ~$129,900

- Chain: BSC

- BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 2: Access Control Vulnerabilities - Primary Classification:

BWC 2.1.1: Missing Access Control - Secondary Classification:

BWC 5.2.1: Price Manipulation(Atomic Sandwich)

- Broader Classification:

- Description:

- Note: This incident occurred in late 2025.

- The MSCST staking contract on BSC was exploited for ~$129.9k via an atomic sandwich attack facilitated by a public function.

- Vulnerability: The

releaseRewardfunction lacked access control, allowing any caller to trigger internal logic. Additionally, the function allowed the caller to specify afeeparameter (or implicitly used the contract's balance) to execute a swap. - Attack Flow:

- Flashloan & Dump: The attacker flashloaned GPC tokens and swapped them for BNB, lowering the price of GPC.

- Trigger Vulnerability: The attacker called

releaseRewardwith thefeeset to the contract's MSC balance. This function swapped MSC for GPC and transferred the GPC directly to the GPC/BNB liquidity pool (callingsync), effectively increasing the GPC reserves and further lowering the price (making GPC cheaper). - Arbitrage: The attacker swapped their BNB back for GPC at the artificially lowered price, profiting from the spread, and repaid the flashloan.

- References:

2025-12-24 - 4

- Date: 2025-12-24

- Project: EIP-7702 Delegatee Contract (Unnamed)

- Value Lost: ~$280,000

- Chain: BSC

- BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 10: Network & Consensus Evolution Attacks - Primary Classification:

BWC 10.4.1: EIP-7702 Delegation Risks(Initialization Front-Running) - Secondary Classification:

BWC 3.2.1: Improper Initialization

- Broader Classification:

- Description:

- An uninitialized EIP-7702 delegatee contract was exploited on BSC, resulting in a loss of approximately $280,000.

- Vulnerability: The contract, intended to serve as a code source for EIP-7702 delegations, was deployed without being initialized.

- Attack Flow: The attacker called the exposed initialization function to grant themselves the owner role of the delegatee contract. Once in control of the logic contract, they were able to manipulate the accounts that had delegated to it, effectively draining the funds from the delegators.

- Aftermath: The stolen funds (~95 ETH equivalent) were subsequently deposited into Tornado Cash.

- References:

2025-12-21 - 3

- Date: 2025-12-21

- Project: CHAR (Token Pair)

- Value Lost: ~$144,500

- Chain: BSC

- BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 5: Economic & Game-Theoretic Vulnerabilities - Primary Classification:

BWC 5.1.2: Back-Running(MEV Skimming) - Secondary Classification:

BWC 1.1.7: User Disempowerment(Operational Error / "Fat Finger")

- Broader Classification:

- Description:

- A user or project team member suffered a loss of ~$144.5k involving the CHAR token on BSC.

- Vulnerability: This was an operational error rather than a smart contract flaw. The victim mistakenly transferred CHAR tokens directly to the Uniswap V2-style liquidity pair address instead of interacting with the router to swap them.

- Execution: The liquidity pool contract's balance became greater than its tracked reserves (sync mismatch). An MEV bot detected this discrepancy and executed a transaction (likely calling

skim()or a swap) to extract the excess tokens, effectively claiming the "donated" funds.

- References:

2025-12-19 - 2

- Date: 2025-12-19

- Project: Dragun69

- Value Lost: ~$87,400

- Chain: BSC

- BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 3: Smart Contract Logic & State Manipulation - Primary Classification:

BWC 3.3.3: Improper Handling of Native Tokens(Missingmsg.valueCheck) - Secondary Classification:

BWC 4.1.1: Insufficient Input Validation

- Broader Classification:

- Description:

- Note: This incident occurred in late 2025 but was logged in the 2026 database due to disclosure/reporting timing.

- The "Dragun69: Router" contract on BSC was exploited for ~$87.4k due to a missing validation check on native token transfers.

- Vulnerability: The router's swap function (specifically for ETH -> Token swaps) failed to verify

msg.value. The contract logic assumed that the BNB amount specified in the swap parameters was provided by the caller in the current transaction. However, without the check, the contract utilized its own accumulated BNB balance to execute the swap. - Attack Flow:

- Trigger: The attacker called the Aggregator Proxy, which triggered the vulnerable implementation to run a PancakeV3 swap.

- Misappropriation: The router, failing to check

msg.value, spent its own WBNB/BNB reserves to fulfill the swap. - Extraction: The swap callback verified the balance and forwarded the resulting tokens/BNB to a recipient address specified in the untrusted calldata (the attacker), effectively draining the contract.

- Note: The project's deployments on Base and Ethereum were not affected as they correctly included the

msg.valuecheck. The BSC implementation was patched ~6 hours after the exploit.

- References:

2025-12-13 - 1

- Date: 2025-12-13

- Project: Ribbon Finance (Legacy Contracts / Opyn Fork)

- Value Lost: ~$2,700,000

- Chain: Ethereum

- BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 2: Access Control Vulnerabilities - Primary Classification:

BWC 2.1.1: Missing Access Control(Unprotected Oracle Configuration/Ownership) - Secondary Classification:

BWC 4.2.2: Oracle Manipulation

- Broader Classification:

- Description:

- Note: This incident occurred in late 2025.

- Legacy contracts associated with Ribbon Finance (specifically an Opyn fork) were exploited for approximately $2.7M.

- Vulnerability: The root cause was identified as a flawed oracle upgrade. Approximately 6 days prior to the attack, the oracle pricer was updated. This update reportedly introduced an access control vulnerability (potentially involving an unprotected

transferOwnershipor insufficient checks on the pricer whitelist logic) that allowed the attacker to manipulate price-feed proxies. - Attack Flow:

- Market Creation: The attacker created a new option market (e.g., LINK/USDC) with a short expiration time.

- Oracle Manipulation: Abusing the vulnerable oracle stack, the attacker forced arbitrary expiry prices for assets like wstETH, AAVE, LINK, and WBTC into the shared Oracle at the specific expiry timestamp.

- Drain: The attacker redeemed large short oToken positions against the MarginPool. Because the MarginPool relied on the forged expiry prices for settlement, the attacker was able to drain WETH, wstETH, USDC, and WBTC.

- References:

2025-11-20 - 5

- Date: 2025-11-20

- Project: GANA Payment

- Value Lost: ~$3,100,000

- Chain: BSC

- BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 10: Network & Consensus Evolution Attacks - Primary Classification:

BWC 10.4.1: EIP-7702 Delegation Risks - Secondary Classification:

BWC 1.2.2: Private Key Leakage,BWC 2.1.1: Missing Access Control

- Broader Classification:

- Description:

- GANA Payment, a newly launched payment protocol on BSC, was exploited for $3.1 million just nine days after launch.

- Root Cause: The exploit originated from a compromised owner private key. The attacker used this key to authorize an EIP-7702 delegation to a malicious contract.

- The Exploit: The malicious delegator contract acted as a middleman, allowing the attacker to bypass the

onlyEOA(tx.origin == msg.sender) check on the staking contract. Because the transaction was an EIP-7702 transaction authorized by the owner, the staking contract perceived the calls as legitimate EOA interactions from the owner. - Attack Flow:

- Access: Compromised the owner key.

- Delegation: Transferred ownership to 8 different addresses, each authorizing the malicious EIP-7702 delegator.

- Manipulation: The delegated code manipulated the

gana_Computilityreward rate to an astronomical value (10,000,000,000,000,000). - Drain: Systematically staked and unstaked funds through these accounts, draining the protocol.

- Aftermath: $2.1M was bridged to Ethereum, and ~$1M was laundered through Tornado Cash on BSC.

- References:

2025-11-11 - 4

- Date: 2025-11-11

- Project: @ImpermaxFinance

- Value Lost: 380,000 $

- Chain: base

- BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 6: Arithmetic & Numeric Vulnerabilities - Primary Classification:

BWC 6.2: Precision Loss & Rounding Errors - Secondary Classification:

BWC 2.1.1: Missing Access Control

- Broader Classification:

- Description:

- The exploit was a sophisticated, multi-stage attack that combined a precision loss vulnerability in the liquidation mechanism with a missing access control on a fund allocation function.

- 1. Precision Loss & State Manipulation: The attacker repeatedly created tiny, "underwater" debt positions in a low-liquidity lending market (cbBTC). By calling the

restructureBadDebt()function, a rounding error allowed them to incrementally drain the market'stotalBalanceone wei at a time. This manipulation drove the pool'sexchangeRateto near zero. - 2. Triggering a Malicious State: The attacker continued this process until the pool's

totalBalancewas exactly zero. This triggered a fallback condition in the code where theexchangeRatefunction returned a default, artificially high value of1e18. At this point, the attacker held nearly 100% of the pool's shares, acquired for a negligible cost. - 3. Missing Access Control & Fund Drain: The attacker then exploited an unprotected

flashAllocatefunction in a separate lending vault contract. This function, which lacked proper access control, was used to force the main cbBTC vault to deposit all its funds into the attacker's manipulated, malicious pool. Due to the artificially high exchange rate, the vault received almost no shares for its large deposit. The attacker, holding all the shares, then withdrew the vault's funds.

- References:

2025-11-04 - 3

- Date: 2025-11-04

- Project: @MoonwellDeFi

- Value Lost: 1,000,000 $

- Chain: base

- BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 4: Input & Data Validation Vulnerabilities - Primary Classification:

BWC 4.2.1: Insufficient Oracle Validation

- Broader Classification:

- Description: Moonwell DeFi's wrsETH price anomaly on November 4, 2025, stemmed from a Chainlink oracle malfunction. The protocol's vulnerability was its failure to validate the data received from its price oracle, blindly trusting an erroneously high price for wrsETH. An exploiter was able to repeatedly borrow over 20 wstETH with only ~0.02 wrstETH flashloaned and deposited due to the faulty oracle that returned a wrstETH price of

$5.8M. The attacker profited by approximately 295 ETH ($1M). - References:

2025-11-03 - 2

- Date: 2025-11-03

- Project: Balancer Hack Side Story (Sonic Chain)

- Value Lost: ~$3,000,000

- Chain: Sonic

- BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 4: Input & Data Validation Vulnerabilities - Primary Classification:

BWC 4.5.1: Parser Differential / Inconsistent Validation - Secondary Classification:

BWC 10.3: Cross-Protocol Interoperability Attacks

- Broader Classification:

- Description:

- On November 3, 2025, following the Balancer V2 hack, the Sonic team attempted to contain the exploit by freezing the attacker's account on the L1 level. They set the attacker's native token balance to zero and replaced their code, intending to prevent them from paying gas to move funds.

- The Bypass (BWC 4.5.1): The attacker bypassed this "transport layer" freeze by exploiting an inconsistency between the L1 gas requirements and the application-level logic. The Beets Staked Sonic (stS) token supported ERC-2612

permit, which allows for gasless approvals via off-chain signatures. The attacker signed apermit(which requires no gas) to authorize a secondary wallet, then used that secondary wallet totransferFromand drain the "frozen" assets.

- References:

2025-11-03 - 1

- Date: 2025-11-03

- Project: Balancer V2 & Forks

- Value Lost: ~$120,000,000

- Chains: Ethereum, Base, Polygon, Sonic, Arbitrum, Optimism, Berachain, Gnosis, Avalanche.

- BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 6: Arithmetic & Numeric Vulnerabilities - Primary Classification:

BWC 6.2: Precision Loss & Rounding Errors - Secondary Classification:

BWC 1.1.2: Permissioning & Censorship Risks,BWC 5.1.1: Front-Running

- Broader Classification:

- Description:

- Arithmetic Vulnerability: The core of the exploit was a precision loss vulnerability within the

upscalefunction in Balancer V2's Composable Stable Pools. This function would incorrectly round down when scaling factors were non-integer values. An attacker utilized thebatchSwapfeature to execute a three-stage attack: first, they precisely adjusted a token's balance to a rounding boundary; second, they performed swaps with crafted amounts, causing the rounding error to deflate the calculated price of the Balancer Pool Tokens (BPT); finally, they swapped assets back to the artificially cheapened BPT for a significant profit. This method was replicated across multiple chains where Balancer V2 or its forks were deployed. - Censorship & Centralized Interventions: Following the exploit, several chains took centralized action. Berachain validators halted the network for a hard fork; Sonic Labs froze the attacker's wallet; Gnosis froze affected pools and suspended its bridge; and Polygon validators reportedly censored the attacker's transactions.

- Front-Running: A white-hat MEV bot operator successfully front-ran some of the attacker's transactions on Ethereum, recovering and returning approximately $600,000.

- Arithmetic Vulnerability: The core of the exploit was a precision loss vulnerability within the

- References:

2025-10-15 - 5

- Date: 2025-10-15

- Project: ZKsync OS

- Value Lost: $0 (Critical Vulnerability Found in Audit)

- Chain: ZKsync Era

- BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 8: Denial of Service (DoS) Vulnerabilities - Primary Classification:

BWC 8.7: DoS via Return Data Bomb - Secondary Classification:

BWC 1.1.1: Indispensable Intermediaries(L1->L2 Queue Halt)

- Broader Classification:

- Description:

- A critical denial-of-service vulnerability was identified in the ZKsync OS execution environment. The system preallocated a fixed 128 MB buffer for

return_datafrom external calls. - The Exploit: An attacker could craft a transaction that makes numerous external calls, returning large amounts of data. This would overflow the preallocated buffer (causing a panic) while remaining within the transaction's gas limit.

- Impact: Crucially, if this panic occurred within an L1->L2 transaction (which are processed sequentially in a queue), it would permanently halt the entire L1->L2 transaction queue. Since the queue processing halts on a panic, no subsequent L1->L2 transactions could ever be processed, effectively bricking the bridge.

- A critical denial-of-service vulnerability was identified in the ZKsync OS execution environment. The system preallocated a fixed 128 MB buffer for

- References:

2025-10-15 - 4

- Date: 2025-10-15

- Project: ZKsync OS

- Value Lost: $0 (Critical Vulnerability Found in Audit)

- Chain: ZKsync Era

- BWC:

- Broader Classification:

BWC 1: Ecosystem & Off-Chain Risks - Primary Classification:

BWC 1.4.5: Client Consensus Bug - Secondary Classification:

BWC 7.4.2: Compiler/Architecture Correctness

- Broader Classification:

- Description:

- A critical non-determinism bug was identified in ZKsync OS during an audit. The issue stemmed from the use of architecture-dependent

usizearithmetic in Rust. - The Flaw:

usizeis 32-bit on the ZK prover's RISC-V architecture but 64-bit on the sequencer's x86_64 architecture. - The Exploit Vector: An attacker could craft a transaction with calldata lengths close to

u32::MAX.- On the Sequencer (64-bit), the transaction processes successfully because the 64-bit integer does not overflow.

- On the Prover (32-bit), the same calculation overflows or panics.